The PSA has been given supervisory responsibility for the safety of offshore wind power (OWP) on the Norwegian continental shelf. In a series of articles, we take a closer look at what OWP involves, risks associated with its development and operation, and how this new industry can be regulated. These reports are taken from our Dialogue magazine.

A modern wind turbine rotates when air speed at the rotor hub lies between three and 25 metres per second. Its output is normally highest with a wind strength of roughly 13 m/s.

The turbine blades can be adjusted to optimise utilisation of the available wind energy, depending on its direction and strength.

Wind-turbine dimensions are growing as the technology advances. The reason is simple – the longer the blades and the larger the area of rotation, the more energy is captured and the more electricity is generated.

Offshore

Winds at sea are often stronger and more stable than on land.

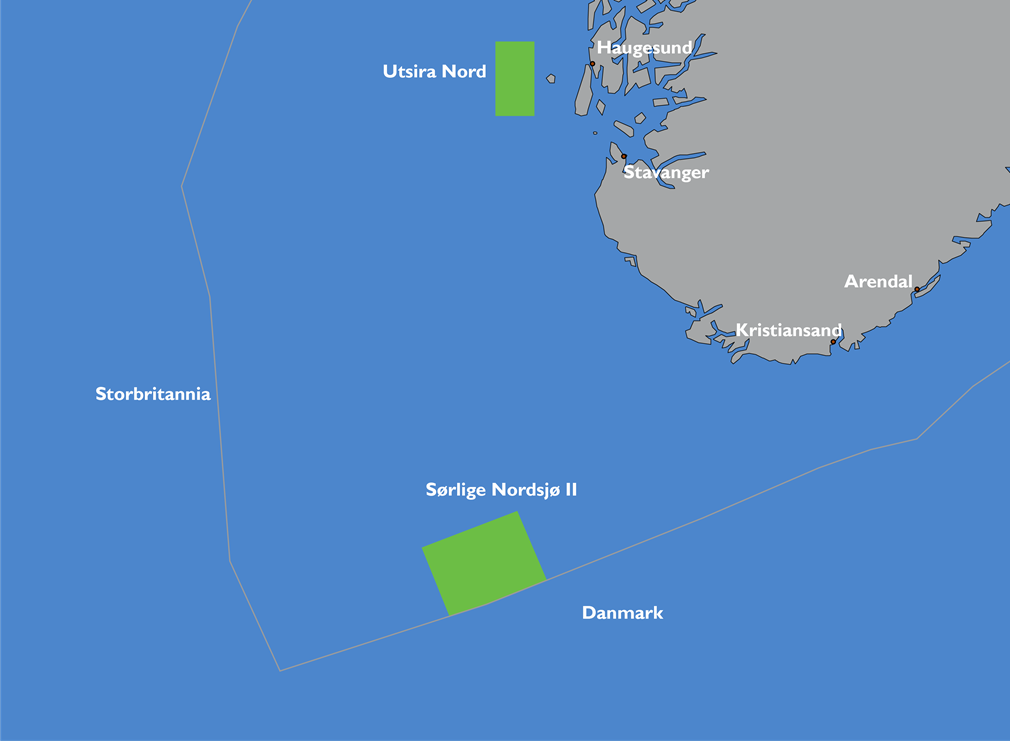

The government has decided to open two areas of the NCS for wind power development – Utsira North, suitable for floating turbines, and Southern North Sea III, which is also appropriate for fixed units.

Water depths on the NCS mean that floating turbines offer the biggest potential for offshore wind power (OWP).

Fixed turbines

Fixed turbines can currently be installed in water depths down to 60 metres, and have so far accounted for the bulk of OWP capacity installed or under construction worldwide.

Many different types of foundations are available for such units, such as jackets, suction buckets and gravity base structures (GBSs).

The choice of solution depends on the water depth and seabed conditions at the turbine installation site.

Floating turbines

Floating turbines must be used today in waters deeper than 60 metres. Various technologies are under development, such as the spar buoy used for Hywind Tampen, semi-submersibles and tension-leg structures.

A common denominator for these solutions is that the floater must provide sufficient stability to cope with high waves, currents and challenging wind conditions.

Leading

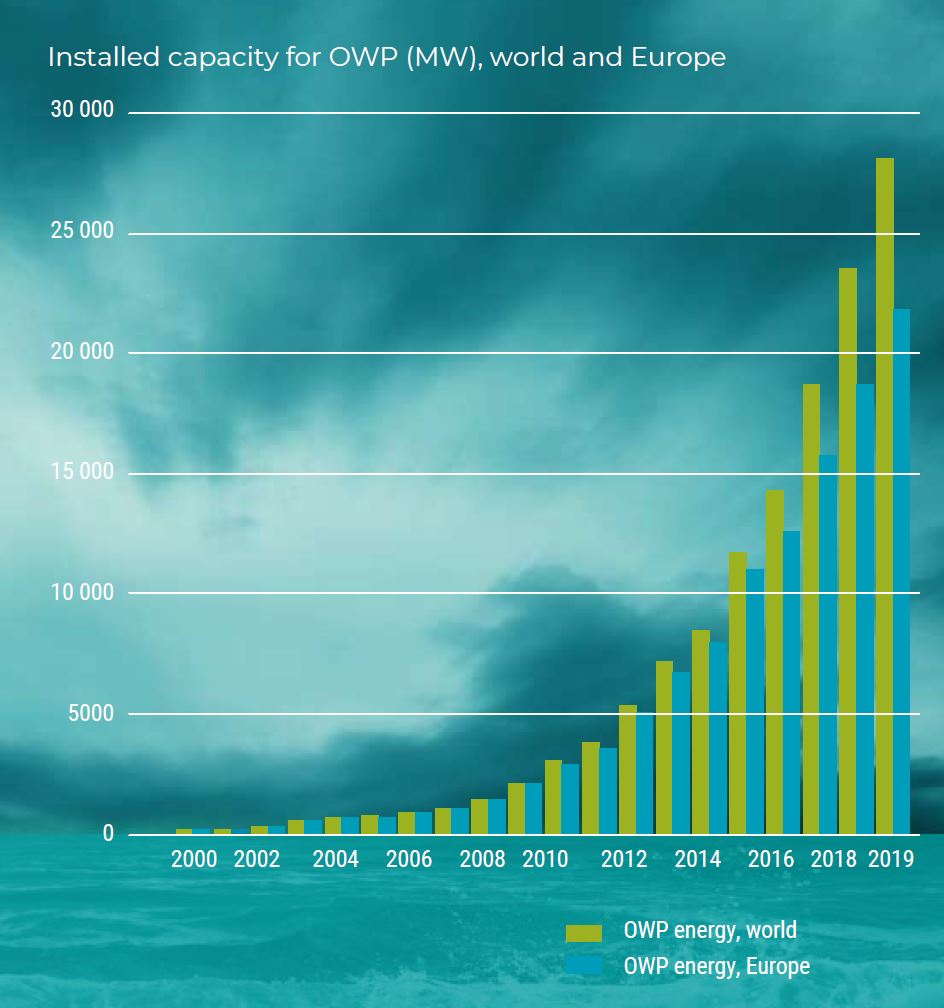

This graph illustrates how the expansion of OWP has gathered pace over the past two decades.

Europe has so far dominated, accounting in 2019 for no less than 21 831 MW of 28 155 MW in total installed capacity worldwide.

The figures come from the International Renewable Energy Agency (Irena).

Sources: Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate, Statkraft, snl.no, Equinor, Ørsted, Irena and regjeringen.no